I set out again on Google and DuckDuckGo to find something about writing and movement. Writing not just for the sake of getting across a row of instructions – but writing to inquire about movement, to solve problems of language, communication, and learning. I’m looking for people who have thought of that before. There must be.

After some searching and sifting through scientific articles I found the relatively new field of Contemplative Pedagogy, „A Quiet Revolution in Higher Education”, as Arthur Zajonc put it, a physicist and the author of several books related to science, mind, and spirit, professor emeritus at Amherst College, and former president of the Mind and Life Institute.

However, I was disappointed about the omission of Somatic Education in Zajonc’s list of classroom practices. It only lists practices such as Mindfulness, Concentration Training, Yoga postures, Pranayama, Sitting in Silence, etc, which all have one thing in common: the absence of movement learning – and acquisition – in the sense of Somatic Education.

Considering the „unreformable” nature of the schooling system (to quote John Taylor Gatto) I can’t help but wonder about Arthur Zajonc’s et al attempts to shine some light into the schooling system; their attempts to change it from inside. The schooling system with its „short-answer tests, bells, uniform time blocks, age grading, standardization, and all the rest of the school religion punishing our nation”, to quote John Taylor Gatto again, from his book „The Underground History of American Education: A School Teacher’s Intimate Investigation Into the Problem of Modern Schooling”.

Instead of „Contemplative Pedagogy”, wouldn’t „Time Scheduled Focus Drills” have been a more descriptive name? Another brick in the wall? Another attempt at getting students to finally be quiet, fit in, and „shut up”? (to quote John Taylor Gatto’s prologue „Bianca, You Animal, Shut Up!”) Or are we indeed witnessing „A Quiet Revolution in Higher Education”? One might still dare to hope.

In Christy I. Wenger’s book, „Yoga Minds, Writing Bodies: Contemplative Writing Pedagogy”, due to its academic nature, I found plenty of references, and also a single 2-page example of contemplative writing about movement, in „Interchapter Three: The Writer’s Breath”, of all chapter titles. I quote:

„»Alright, everyone knows what to do,« I say. »Be sure to sit up straight in your chair and plant your feet firmly on the ground, letting that connection give you a sense of stability and rootedness, like how you feel in tree pose.« Some students shift with these words, but many remain still, already practicing the attentiveness we’ve been cultivating over the past few weeks. They have learned that being relaxed and being attentive are not separate states but can be coupled for greater awareness, and they are using their bodies to achieve this harmony.” – Christy I. Wenger, from „Yoga Minds, Writing Bodies”

This is an interesting find because it’s not a book written by a movement professional, but by Dr. Christy I. Wenger, „Associate Professor of English, Rhetoric and Composition, Director of Rhetoric and Composition” at Shepherd University, Shepherdstown, West Virginia, Department of English and Modern Languages. Therefore, it’s an insight into academia and the state of affairs as of 2015, when this book was published.

Professor Wenger chose to use what I might call „Yoga language”. I have no better name for it, but it seems like most Yoga teachers express themselves like this. It’s a kind of Directive Language, spoken from an expert and authoritative point of view, with very floral metaphors, exaggerations, and claims that would put any vitamins seller to shame if taken at face value.

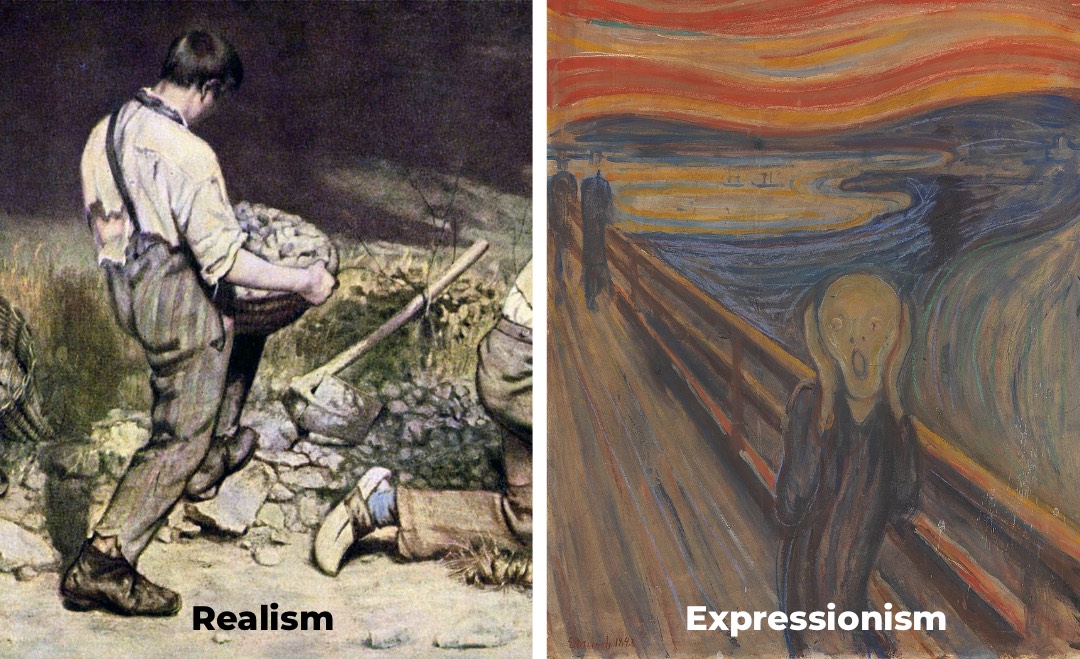

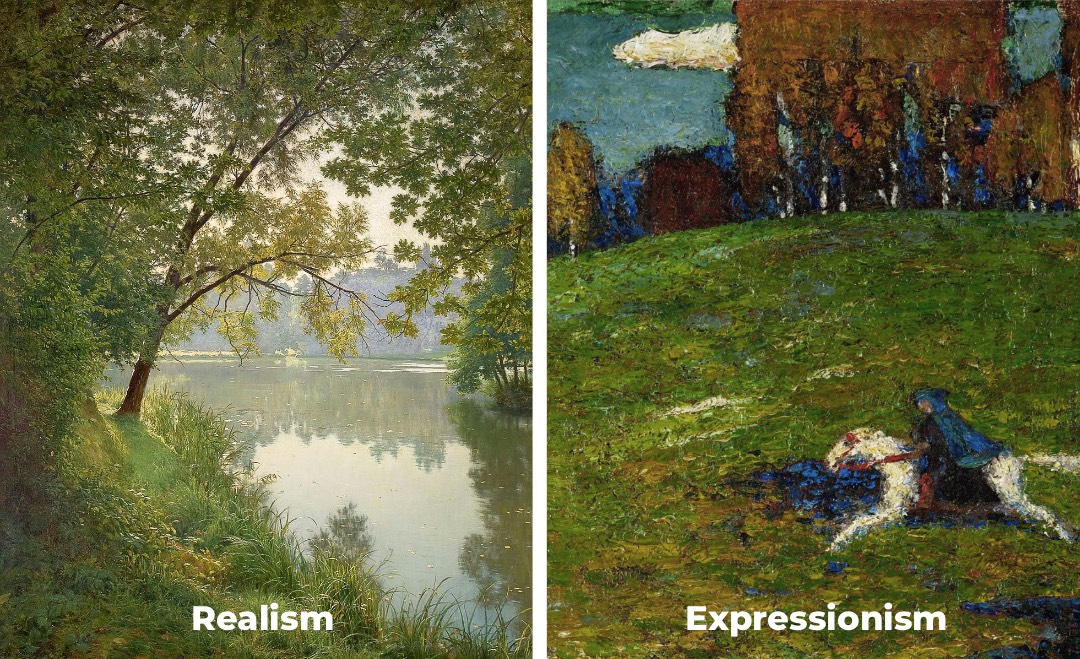

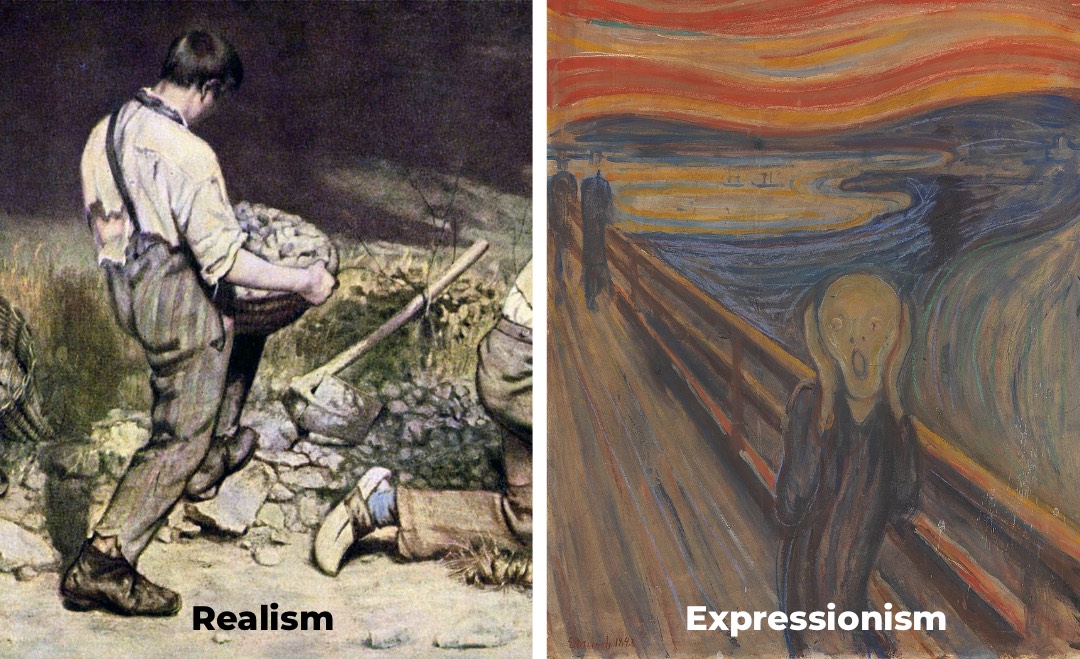

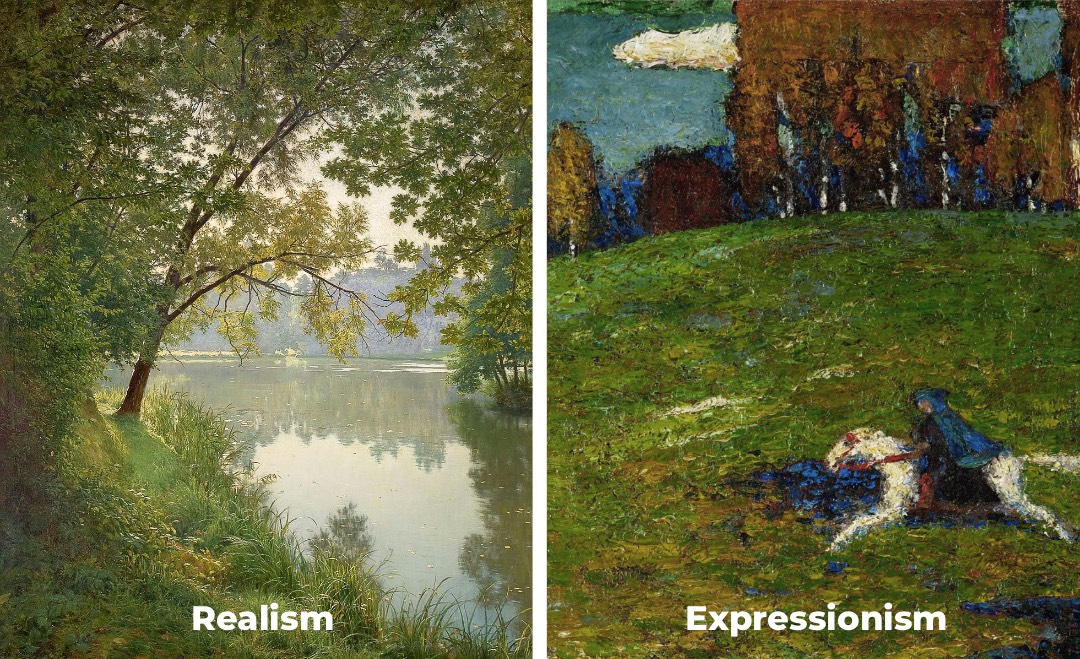

„Yoga language” might be somewhat the opposite of objective descriptions. To paint a picture: in Realism (arts) we would not „plant” the feet firmly on the ground, and that „connection” would not give you „a sense of stability and rootedness”, considering the facts that the feet bear less than a third of the body’s weight in sitting, and that (in the above quoted exercise) a considerable part of the nervous system would be occupied with trying to wilfully sit up straight. This is not a criticism. I would guess that at the beginning of the 20th century many people welcomed Expressionism, and the appreciation of the individuals’ emotions. Where there is light, there is shadow. And even today such floral language might be the counter-weight to, an escape from, the cold and uncompassionate language of scientific studies on movement, range of motion, and biomechanical functioning.

”Realism, sometimes called naturalism, in the arts is generally the attempt to represent subject matter truthfully, without artificiality and avoiding speculative fiction and supernatural elements.” – Wikipedia, on Realism

„Expressionism is a modernist movement. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas. Expressionist artists have sought to express the meaning of emotional experience rather than physical reality.” – Wikipedia, on Expressionism

Paintings: 1. Gustave Courbet, 1849, Les casseurs de pierres (The Stone Breakers) 2. Edvard Munch, 1893, The Scream 3. Henri Biva, ca 1905, Matin à Villeneuve (From Waters Edge) 4. Wassily Kandinsky, 1903, The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter)

I would like to be able to quote Wikipedia on „Yoga language”, but there’s no page for that… yet. I do believe that writing about movement, and to put movement learning – and the experiences thereof – into words, could be something of interest to more than just a few; more than just a few out of the 7.9 billion people that move about on planet Earth as of 2021. After all, all of them, each and every one of them, without exception, had to learn how to roll, turn, sit, twist, stand, walk… move in the way they do.