Backstory

Over the past few weeks I sat on chairs (of all places) a lot, and didn’t do any sports or exercising. But instead I overworked my knees with a few demanding postures, and started to have some knee pain.

Therefore, I decided to take my own medicine, and moved along to my video „Do your hip-joints connect up?” [link] I only did the first 20 minutes and only worked with my right leg. But after getting up, to my surprise, my knee pain was gone.

Two days later I wondered what else I could do with the same movements, and whether I could game-ify the movements of my lesson. A classic balancing game came to mind. It’s called „Labyrinth”, which I have on both my iPhone and Apple TV. It occurred to me that I could try controlling this game with my feet instead of my hands — much like some people paint with their feet instead of with their hands. I gave it a try.

Day 1

On the belly, with knees bent, feet towards the ceiling.

It took a couple of minutes to figure out how to play, but then it actually went quite well. I put on socks and slipped the Siri remote control in between the sole of my foot and the sock to secure it. Then the game was on. It was fun.

However, afterwards, when I checked for any improvements in my left leg, I didn’t register much. Overall my left foot felt a bit softer and more supportive, and my left knee seemed a wee bit more comfortable as well, but by far not as much as with 20 minutes of my movement lesson of Somatic Education on Youtube.

Day 2

I liked the idea of playing a computer game with my foot, though. It was almost like magic to watch the ball on the screen move, without my hands involved. This reminded me of a prank I played on a fellow office worker back in the day when I was a Software Engineer: I placed my computer mouse under the table and controlled it with my foot, out of sight to my co-worker, and pretended to move the mouse pointer on the screen with the power of my mind.

I tried a new position: on the back, with one leg extended, its sole pointing toward the ceiling. This time I used a rubber band instead of socks to secure the remote control on the sole of my foot, which worked a lot better.

Bok choy, was this a challenge. I knew my hamstrings were short—but with this game it really showed. I needed to do some auxiliary movements and some tricks first, just to get the soles of my feet level enough to be able to play.

But then I had a good gaming session, and completed the first 5 beginner levels with each foot. Twice.

Afterwards my legs felt a bit tired, but also light and more flexible than before.

Day 3

Today I was super excited to play the balancing board game again. In the evening I set myself up the same way as the day before: lying on my back, sole facing to the ceiling, with the remote control strapped to my foot with a rubber band.

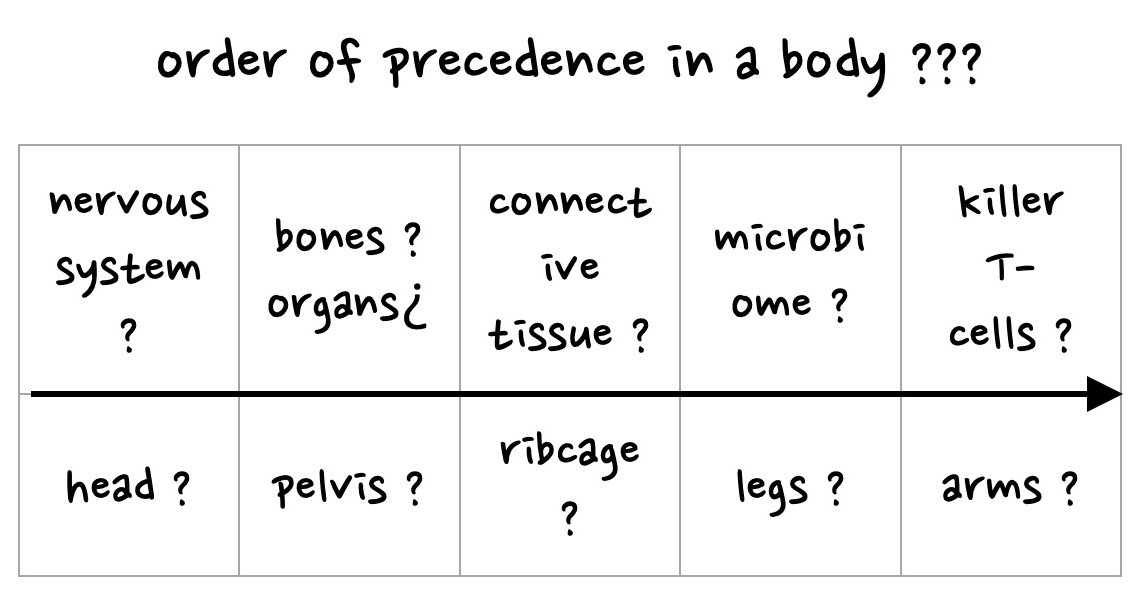

Today the gameplay was smoother than yesterday. I could play more advanced levels. My nervous system seemed to already have learned and adjusted itself to the new gameplay style. Two things stood out:

- Balancing was a lot more steady with my feet than with my hands. This really surprised me. My hands are faster and more flexible, but my feet more steady and more precise. Overall it seems like balance control in this game is better with my feet than with my hands.

- My right leg is not only more flexible than my left, but my right foot is more “dexterous” than my left. This surprised me quite a bit. On the other hand, my left leg is my standing leg, and my right leg my moving leg. Obviously, there’s a handedness to the feet. Actually, no surprises there. But still, surprising to actually feel it as such a big difference.

After playing, my legs felt way more smooth and flexible, and going for a walk was a pleasure. l think this game might be able to solve my hamstrings „problem”. Stretching is out of this world boring to me, so that’s not an option, and I also get bored easily with lengthy Feldenkrais lessons for the hamstrings, but this game (I think) I could play 20 minutes to half an hour on several days a week, no problem.

Day 4 (morning time)

Yesterday evening I went to bed with limber legs and flexible hamstrings, and woke up with legs made from oak hardwoods. Interesting. Why is that? How come my body stiffens up its connective tissue overnight? Is this some kind of internal Settings reset? I mean, I welcome such tightening up for my facial skin, and neck, but for my hip joints and hamstrings… what’s the benefit of tightening up those areas?

Looking forward to play the balance game again tonight, I will keep us posted.