When I first began studying the movement lessons of Moshé Feldenkrais (in the year 2004) I was extremely spirited. I purchased all the class recordings I could get my hands on—which wasn’t nearly enough to satisfy my large appetite. I also exchanged hundreds of “Private Library” class recordings with fellow students. And of course, eventually I also stumbled upon openatm.org (founded by Falk Feddersen) and practiced my way through most of the recordings there.

The recordings that stood out to me most where those of Sharon Moyano (now Sharon Starika). They were in strong contrast to the slow, deep movement explorations I experienced in Feldenkrais professional trainings. To me Sharon’s class recordings appeared to be fast paced, bare bones; only the essentials. One movement—bam!—then the next—bam! To me it was almost brutal, but not as brutal as the movements in the recordings of, for example, Franz Wurm. Sharon’s movement instructions were concise, crystal clear, challenging, and Oh! so good.

In a workshop advertisement (from long ago) teacher Victoria Worsley wrote about Sharon Starika: “The most extraordinary running and Feldenkrais story I have heard is about a professional American triathlete called Sharon Moyano who was hit on her bicycle by a semi. She had nine operations, broke a huge list of bones and lost 3 muscle groups. She was told she’d be lucky to run again and would certainly never race again. For two years she worked intensely with the Feldenkrais Method, doing both classes and one-to-one hands-on sessions. Two years later she beat her own personal best in a marathon by 20 minutes.”

Three days ago I re-visited one of Sharon’s class recordings, 1998/03/10 Elbow Circles Holding the Chin, and had the same feeling again: bare bones, only the essentials, almost brutal, but Oh! so good. Of course- I felt inspired. The lesson improved my breathing as well as the mobility of my chest. It improved my ability to bring my arms overhead and it got me into being more aware of my arms (and upper chest) in walking. It actually got me so excited about my upper limbs that I started a practice of throwing tennis balls against a wall; which I enjoy greatly. If only I had discovered this as a teenager I might have enjoyed playing tennis later on.

However, I wouldn’t dare to teach Sharon’s movement sequence to a general audience via recorded video. I would worry over Youtube viewers at home trying such a video with frozen shoulders, or a shoulder impingement, or being post shoulder surgery (or any other condition a doctor would have a name for). To teach this lesson myself I would need to make some changes, make it suitable for a general audience. But first I would need to put Sharon’s lesson to the knife and sample the key strategies:

The lesson starts with a reference movement. How well do your arms extend overhead to rest on the floor?

The first movement is to pull on a wrist (or fist), with your hands behind your head. One side first, then the other.

You then push one foot against the floor to roll into side-lying, and continue the same pulling on one wrist in side-lying. Your head rests on the floor (on its temple) in front of the arm that touches the floor, and you pull that arm’s elbow up towards the ceiling.

Next you sit cross legged. Your hands are behind your head, and with your left hand you pull on your right wrist to get hold of your chin on the left side of your face. Only now we get the cue to focus on the elbows and how we move them through space in relation to… well, there’s like 6 or so variations of this.

The last strategy is on the belly, in prone position. The hands—first one by one and then in unison—slide down the neck, over the shoulder blades, towards the lower back. May the elbows touch together?

Ok- my surgical dissection of Sharon’s lesson is done. I hope now you too can see the lesson clearly. The strategies, the positions and the reasons for the various positions, the constraints and possibilities. How a glued up shoulder and upper chest is invited into movement without the use of classic stretching, elastic bands and kettle-bells. And how the movements of the shoulders are brought into relation to the rest of the body. I would think that for many people these movements are difficult, hard to do, but nevertheless it’s a wonderful, quite intriguing sequence.

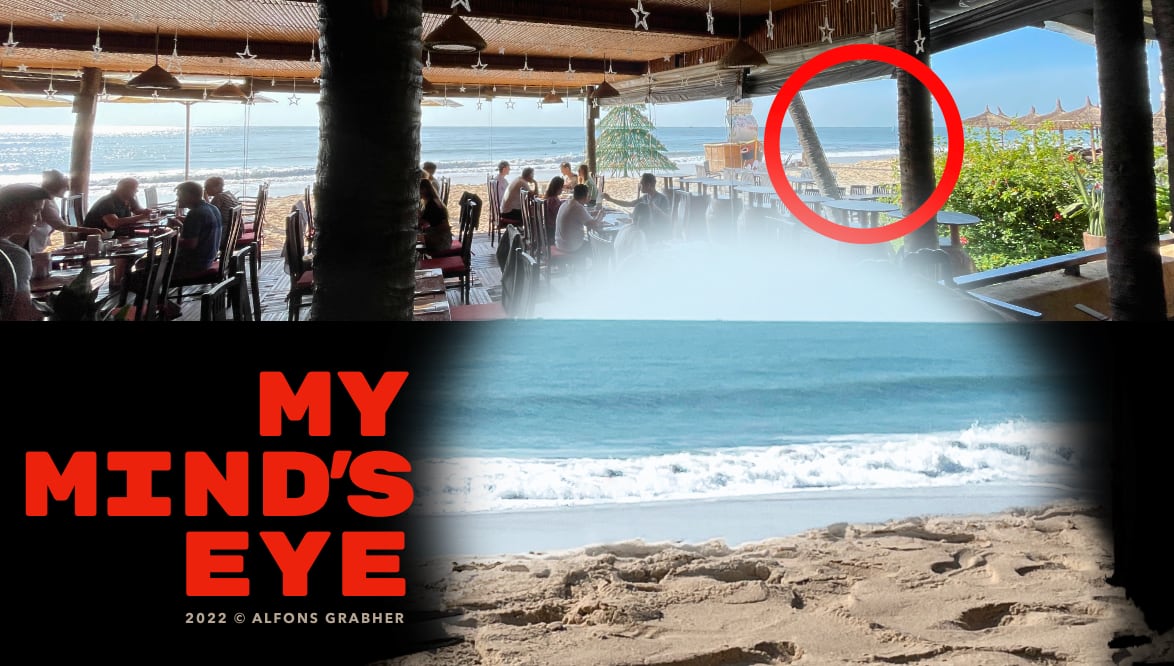

I was riding my 🛵 to a ☕️ shop, where I now sit and write this blog post. While driving I was thinking that a very flexible person might look at these movements and say, “So what, I can easily do all of these.” Probably a quite stupid, imaginary conversation with myself in my head. But there I was, searching for a metaphor in the crypts of my brain… that’s like someone picking up a book, for example Harry Potter Volume 1, and saying: “So what, I can easily read all of that.”

Here’s the adaptions I would introduce:

I would change the reference movement, to turning the head. And how well that movement is connected to the chest, and how (and if) the chest moves at all while turning the head. A side-bending, a twist, a shortening and lengthening, maybe the pelvis tilts sideways, maybe the even the legs move? And I would ask about the breathing in the upper part of the chest. I might keep the arms-over-head as a test, but wouldn’t make it the main reference movement, the main point of the lesson.

I would have the hands relaxed, and pull on a wrist rather than a fist. I would cue to focus on the movements and trajectories of the elbows already, and not wait until later in the lesson. I would start into the first movement with approximations: the hands in-front of the chest. I would allow the head to follow, to react, to roll. I would observe the movements of the chest and my breathing. With each pull I would bring my wrists further up in-front of my face, and then over head, and only eventually behind my head. Only then I would lift my head, and it will stop rolling, because it’s now lifted, the neck and chest under tension like a hoisted sail on a sail boat.

I would use more time for the rolling into side-lying. I would bring attention to how my head is carried over—or even lifted over—the arm that’s on the floor. How the lifting of my head will lengthen the side that’s pressing against the floor, and at the same time shorten the side that’s facing the ceiling. And how I would press my side against the floor to lift my head.

I would think about the elbows again. How my elbows can move my upper chest, neck and head in lines and circles. How my head can push my arm around (the arm that’s on the floor), backwards. How my whole body extends and flexes and twists and moves to point my elbow.

I would start holding my chin in lying on the back, and not in sitting. In this way it’s easier to get the whole chest to move, instead of risking the movement being done mostly in the neck only. The middle of my back presses against the floor, my pelvis can tilt backwards, my right elbow can point towards the right foot (or the left, etc.) After all, in Youtube videos I cannot see my students and this progression is safer for both, my student’s necks and my teaching goals.

For the part that’s done in sitting, I would not guide students through all 6-or-so variations. I think it’s just too much. I would introduce some ideas and leave it up to the students what they do with it. Keep it simple, and allow time and space for their own discoveries and explorations. Maybe someone will turn it into a rolling lesson, so be it, great fun!

Lastly, before wrapping things up, again I would start with a lose lifting of the elbow, borrowing parts of that classic Feldenkrais extension lesson, to ease into sliding the hand down the neck and over the shoulder blade towards the lower back. With a mode of easiness. Instead of focusing on the actual movements, I might try to drive students towards observing their movement learning and their building-up of consciousness.

Ok- that’s all I have for today. A demonstration of how I would listen to another practitioner’s teaching; of how I would analyse, modify and adapt a movement sequence for myself and for my own teaching.