So I went ahead to identify the types of instructions we use in Somatics classes, especially in the style that’s inspired by Moshé Feldenkrais, a pioneer of somatic education.

Each type of instruction has its reason to be there, its story, its rules, scope and limits, its pedagogical, bio-mechanical and neuro-scientific reasoning. The occurrence and frequency of the types is generally not fixed, but happen in response to the class, like in a lively conversation.

A lot could be said and written about each type of instruction. Maybe this could be worthwhile for a book; or for designing a study course for scholars of somatic education.

Here’s the list I’ve made. Types of instructions are in bold print, followed by one or more sentences as they could occur in a class, which typically might be called “lesson”:

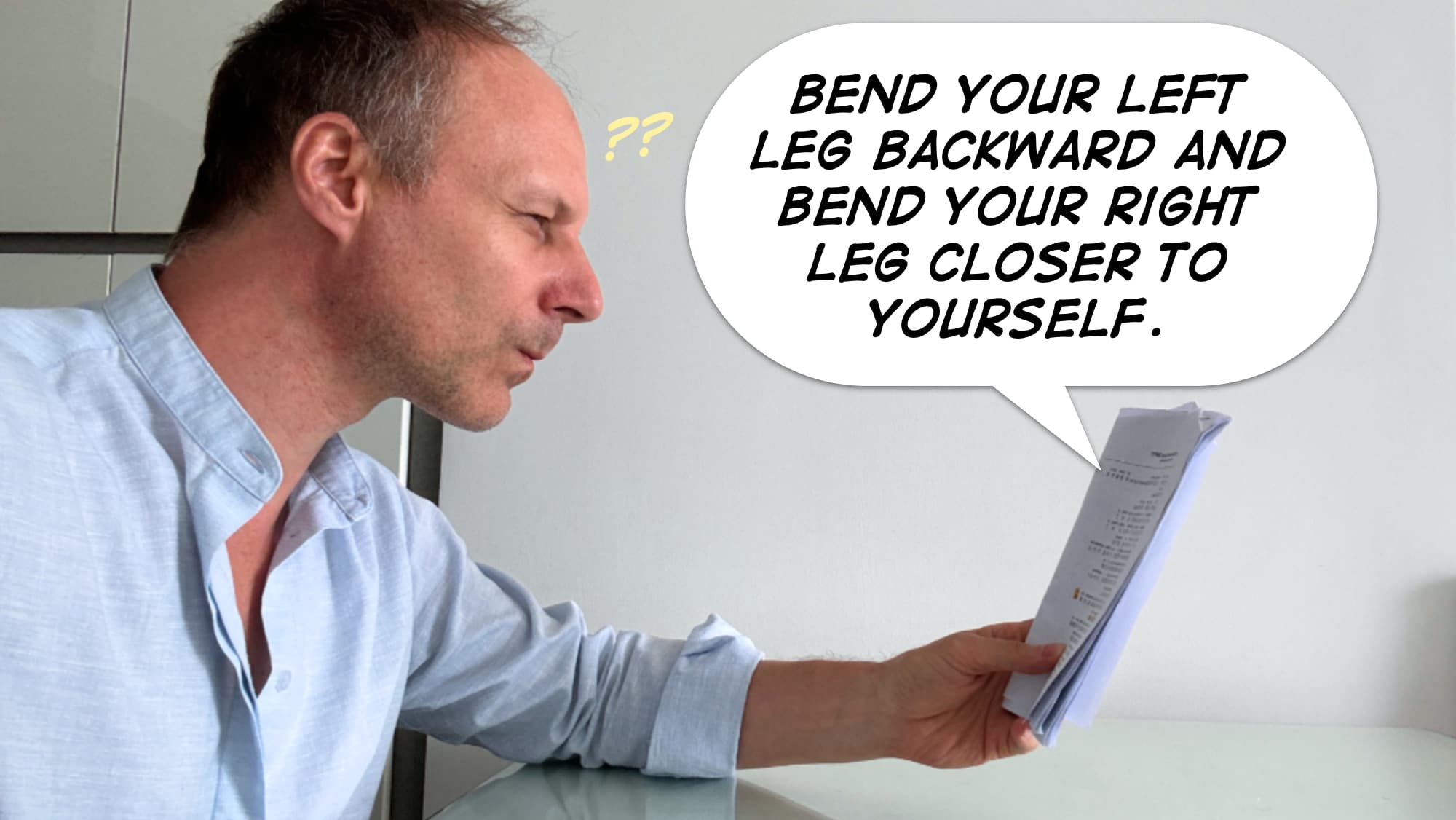

Instruct how to move into the starting position, step by step

- “Please sit on the floor.”

- “Bend your left leg backward and bend your right leg closer to yourself.”

- “With your right hand lean on the floor.”

- “Place your left hand on your head.”

Describe how the position should look like

- “Your left hand is on the top of your head.”

- “You are leaning on your right hand with a straight elbow.”

Point out unintended positions and how they should be done instead

- “Your left hand is not behind your head, but on top of it.”

- “Your left elbow is not pointing forward in the same direction as your nose, but to the left, as is your left ear.”

- “You are properly leaning on your right hand, and not just pointing it down to touch the floor lightly with your fingertips.”

Instruct the movement

- “Move your head right and left.”

Give alternative instructions for the same movement

- “Bring your right ear closer toward your right shoulder and then your left ear closer toward your left shoulder.”

Point out which movement options you want to exclude, and what to do instead

- “Don’t turn your head, but bend it right and left.”

- “Don’t turn your upper body, but pay attention so that you bend exactly right and left.”

If there’s too many possibilities for students to go into unintended or irrelevant movements you might want to use clearer, more descriptive (for example “your left earlobe toward the tip of your left shoulder”), less ambiguous instructions, or introduce stronger constraints*, instead of loosing your cool.

(*) “constraints” is a technical term of somatic education. It refers to limitations introduced via postural choices, such as lying on the back, side-sitting, leaning on one hand etc, to guide movements in a particular direction. In somatic education, constraints are often used to help students focus their attention and movements more effectively.

Describe the quality of how to move

- “Do very light movements.”

- “Do not rush.”

- “Don’t push yourself.”

- “Don’t try to do a lot.”

- “Do the movements clearly.”

Describe how the movement connects to other areas of the body, encourage students to observe and acknowledge that

- “Notice that when you bend your head to the left, your left buttock lifts further away from the floor. Let it do that.”

- “Notice that when you bend your head to the left, the left side of your chest shortens and the right side lengthens. The ribs on the left side move closer to each other, and the ribs on the right side spread further apart.”

- “Allow your left buttock to lift when you bend your head to the left, and to return down toward the floor when you bend your head to the right.”

Give tactile cues and affirmations that could help with moving and understanding

- “Sense and observe the movements of your left buttock in relation to the floor.”

- “All of your spine will bend and help your movements.”

- “Slowly, slowly, your pelvis will move more, and more.”

Give explanations why something might be happening

- “Your chest and spine are becoming more supple because you move as a whole, in all areas, gently and slowly.”

- “Your left buttock will move up and down more, with ever more lightness and freedom, because your whole chest and spine, including your neck, are becoming more supple.”

Keep quiet to allow students time to explore and discover

- “…”

Notify students about the end of this section of the lesson and tell them in which position you prefer them to rest

- “Leave this and rest on your back.”